While there are many tourist destinations that represent the Indigenous culture outside of those discussed in this blog, it is important to remember while experiencing them to keep open a critical eye. As proved through my exploration of tourist destinations, the myth of the ‘vanishing Indian’ is still very present through western society, and not always easy to spot. Whether you are in theme parks, museums, casinos, or ‘authentic’ Indigenous communities, it is vital to take every experience with a grain of salt and some critical thinking. There are countless tourist destinations which offer guests a glimpse into Indigenous culture, however it is important to remember that not all that is represented is truth.

Home » Articles posted by emilydafoe

Author Archives: emilydafoe

“Authentic” Indigenous Experiences

When visiting the Aboriginal Tourism BC website I was struck with how many experiences are available in British Columbia. In one aspect of this site viewers can read through a list of tourist experiences that are “Authentically Aboriginal” (Authentic Aboriginal). There are many issues with this because it is discounting all other experiences offered on this site as invalid. British Columbia, Canada, is a place where, as the above web page shows, has a lot of Indigenous culture present.

The above video was produced by Aboriginal Tourism BC, and showcases some of the available experiences of Indigenous Tourism. As well as offering insight into the economic side of the Indigenous Tourism of British Columbia.This video states that the majority of visitors to Indigenous Tourism are “Educated, upper middle-class, […] [and are] spending more money per trip than other tourists” (Aboriginal Tourism BC – showcasing the experience). Mentioning the education of tourists give off a strange impression of the assumed superiority of the tourists.

One of the “Authentically Aboriginal” places guests can visit includes the Xatśūll Heritage Village. Activities at this establishment includes sweat houses, craft workshops, guided tours,

meals, and accommodation. As the website claims, “The Xatśūll community invites you to visit and experience their spiritual, cultural, and traditional way of life. There are regularly scheduled daily tours and you can take part in a variety of educational and recreational activities each day” (Cultural Tours with First Nations Guides of the Northern Shuswap). Through the entire Xatśūll Heritage Village website there is a strong emphasis on the ‘historical’ and ‘traditional’ aspect of the experience that is offered at this location. This brings us back to the myth of the ‘Vanishing Indian,’ because allowing for tourist’s experience of Indigenous culture to have a focus remaining on the past, the myth is being perpetrated. Giving the tourists the idea that this culture lives, but lives in the past.

As argued in Mary Louise Pratt’s Imperial Eyes, “[Encounters] treat the relations among colonizers and colonized, or travelers and “travelees,” not in terms of separateness or apartheid, but in terms of copresence, interaction, interlocking understandings and practices, often within radically asymmetrical relations of power” (Pratt 7). This holds true while investigating these “Authentic” experiences offered across North America. This is due to the inclusiveness that can be felt for the tourists who visit these locations. These experiences can be seen to create a sense of understanding of Indigenous culture that can be felt by the tourists. Yet, in reality the culture that is being presented, while not inaccurate, does not seem to tell the whole story of the culture. These establishments show the guests many great things, for instance, how the traditions of these cultures have survived, yet seem to leave out the adaptation of the culture, as every culture does, for the modern world. This type of evolvement can be seen through many works of Indigenous fiction, for instance, Lee Maracle’s First Wives Club Salish Style. This collection of fictional short stories discusses and explores an Indigenous culture that lives in the present and not in the past, proving the ‘Vanishing Indian’ myth wrong. Every story within Maracle’s work deals with issues within the contemporary western society, but from an Indigenous perspective.

By exploring what are said to be “Authentic” experiences of Indigenous culture, it is clear that these experiences could easily be seen as doubtfully authentic. This is due to the strong historical basis for these experiences. There is a danger in this because this gives the tourists the idea that what they are seeing is the truth, and makes them believe that they then have a correct understanding of this culture, because it is advertised as “authentic.” However, it should be noted that the idea of ‘Authentic’ for the Indigenous Culture may differ from the concept of ‘Authentic’ for the tourists. Because of this it is important to remember to keep a critical eye open when experiencing what is said to be an ‘authentic’ experience, because it can be seen that the ‘vanishing Indian’ myth is unfortunately still alive and strong within the tourism industry.

Works Cited

Maracle, Lee. First Wives Club: Salish Style. N.p.: Theytus Books, 2010. Print.

Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. New York: Routledge, 1992. Web. 18 Nov. 2013.

“Welcome.” Cultural Tours with First Nations Guides of the Northern Shuswap. Xatsull Heritage Village. Web. 1 Dec. 2013. .

“Xatśūll Heritage Village.” Aboriginal Tourism BC. Aboriginal Tourism BC. Web. 1 Dec. 2013. <http://www.aboriginalbc.com/members/xatsull-heritage-village/>.

The Impact from Indigenous Culture on Casinos

It is a stereotypical view that casinos are a hotspot for Indigenous culture. While there are many casinos around the world that are void of Indigenous Culture, many however are situated on Indigenous land, and are thus run by different Indigenous cultures. As Piner and Paradis cite in

their article, “Beyond the Casino: Sustainable Tourism and Cultural Development on Native American Lands”, the Indigenous Yavapai-Apache nation’s casino Cliff Castle Casino “sits on the brink of self-determination and financial independence […] [and has] developed a solid foundation in community, cultural preservation, social services and economic diversification through the use of casino gaming” (Paradis Piner 82). This casino provides a great example of a tourist destination that is run and created by Indigenous communities. These establishments provide work and jobs to those of the community, and allow for economical prospering. For example, if looking at the job application process for this establishment there is an aspect of the application that specifically asks for the applying party’s heritage. These casinos are able to present the guests with a representation of their culture while also presenting it in an enviroment which is very modern, disproving the ‘Vanishing Indian’ myth.

As stated in David Newhouse’s ‘Resistance is Futile: Aboriginal Peoples Meet The Borg of Capitalism,’ “as contemporary Aboriginal peoples, we now live within a capitalistic system, within a market economy. And that our economic development will occur within that system” (Newhouse 147). Newhouse’s argument is very valid while discussing Indigenous run casinos because that is what is occurring. It seems that Indigenous culture have found an industry that both benefits their community through economy as well as the sustaining of their culture. Casinos allow for Indigenous peoples to present their culture to a mass public on their terms and how they choose to.

Returning to the influence that tourist spots have on the myth of the ‘Vanishing Indian,’ as mentioned in my previous post in which I discussed museums, it seems that tourist destinations that are operated by indigenous culture presents a very different representation of the culture than those operated by non-Indigenous. As mentioned above casinos offer Indigenous cultures with the chance to work at disproving the ‘Vanishing Indian’ myth, and that is through their involvement in the operating of casinos.

These establishments allow for reclaiming of their Identity and culture by being able to present it on their own terms. As seen in Joseph Boyden’s novel Three Day Road, tradition works when it is used as a guide for the future, and as a tool for the reclaiming of a dying culture. Casinos act in the same way, as the communities are able to use their traditions and culture as a guide for the future. Moreover, casinos allow for Indigenous cultures to fight against the myth of the ‘Vanishing Indian,’ and for a representation of the culture that shows the modernity of this culture, while they are also holding onto their past traditions and culture.

Works Cited

“Application for Employment.” Cliff Castle Casino and Hotel. Cliff Castle Casino and Hotel. Web. 26 Nov. 2013.

Boyden, Joseph. Three Day Road. Toronto: Penguin Group, 2006. Print.

Newhouse, David. “Resistance is Futile: Aboriginal Peoples Meet The Borg of Capitalism.” Ethics and Capitalism (1999): 141-55. Web. 26 Nov. 2013.

Paradis, Thomas W., and Judie M. Piner. “Beyond the Casino: Sustainable Tourism and Cultural Development on Native American Lands.” Tourism Geographies 6.1 (2004): 80-98. Scholars Portal. Web. 26 Nov. 2013.

The Issue of Museums

On a recent trip to New York I was able to visit the American Museum of Natural History, while keeping the idea of Indigenous tourism in mind, I found their treatment of this culture to be shocking. The first thing that struck me in the treatment of natives in this museum is that they are refered to as ‘Indian’ on the signs throughout the museum. This museum however, does not only deal in the past, they also have an entire area dedicated to the exploration into outer space, however their Indigenous representations are very much in the historical side of the museum. In Mary Louise Pratt’s Imperial Eyes she states, “natural history catalyzed each other to produce a Eurocentered form of global or, as I call it, ‘planetary’ consciousness” (Pratt, 5). This is what is a play in the Museum of Natural History, because there is a strong sense of authority that is taken over history, that in many cases in not the accurate truth.

The scene as pictured above is one of the many representations of Indigenous culture that is present in the American Museum of natural history. This scene is called, “Old New York,” which clearly shows the idea of the ‘new world’ meeting the ‘old,’ old being represented by the Indigenous men in this image.This image from the Museum of Natural History is one of many representations of how Indigenous culture is being historicised through their representations.

The image to the right is another representation of the Indigenous culture. Through looking at this image it comes off very clear that there is an idea that the aspects of Indigenous culture that are very important to their culture belong in museums. Traditionally museums are meant to teach about the past, and by placing these items behind glass walls gives the impression that they are historical, and has no place in the modern era, furthering the myth of the ‘Vanishing Indian.’

In contrast to this museum, The Museum of Contemporary Native Arts showcases that Indigenous culture is not of the past. This museum is located in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and “is dedicated solely to advancing the scholarship, discourse and interpretation of contemporary Native art for regional, national and international audiences” (About MoCNA). This museum collects items that date from 1962 and onward (About MoCNA), and provides a wonderful alternative to Museums such as the Museum of Natural History. This museum works to “establish an Indigenous discourse that reflects the vibrancy and potency of the contemporary Native arts field at its most current level of activity” (Vision Project). This establishment works in a way that breaks down the myth of ‘Vanishing Indian’ because this museum is able to show the survival of this culture. The video below showcases that, because it is able to exhibit the continual building of Indigenous Culture through their art.

The importance for stories is something vital to every culture, and the Indigenous culture is not exception. Indigenous stories are a way of teaching, and that is something that cannot be overlooked. Mourning Dove’s Cogewea, is an example of this because through reading this novel, the reader understands that Mourning Dove understood the importance of stories. Mourning Dove understood the importance of language’s use to teach, because that is all we have (Humphreys). The coffin the Indigenous culture is placed in through their presence in museums is a way of killing that culture, because the museums are in many ways washing away their stories, and gives the culture a dead historical sense. But there are museums that work to counter this through the showcasing of modern Indigenous culture, like the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts. What it really comes down to with the Indigenous culture’s presence in museums is the treatment of Indigenous culture. It is vital for museums to work to break down the myth of the ‘Vanishing Indian,’ but the ugly truth of matter is that the majority of museums of western culture do not do this, thus sadly, furthering the myth of the ‘Vanishing Indian.’

Works Cited

“About MoCNA.” The Museum of Contemporary Native Arts. The Museum of Contemporary Native Arts. Web. 18 Nov. 2013. <http://www.iaia.edu/museum/about/>.

Humphreys, Sara. “Why Mourning Dove Wrote a Western.” Trent University . Oshawa. 30 Sept. 2013. Lecture.

Mourning Dove, Mourning Dove. Cogewea. N.p.: University of Nebraska Press, 1981. Print.

Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. New York: Routledge, 1992. 5. Web. 18 Nov. 2013.

“Vision Project.” The Museum of Contemporary Native Arts. The Museum of Contemporary Native Arts. Web. 18 Nov. 2013. <http://www.iaia.edu/museum/vision-project/>.

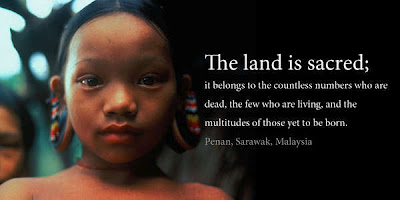

On the tip of the tipping point – when ecology is understood to be spiritual, there’ll be no going back.

An interesting take on Indigenous tourisim.

A core tenet of Conscious Travel is an understanding that each place is alive and sacred.

Host providers will develop truly sustainable livelihoods that benefit their communities when they come into right relationship with all life.

Our indigenous brothers and sisters have always understood this and now find themsleves on the frontline of a global clash in world view:

- one perspective considers all it views to be dead matter that exists for our manipulation and exploitation (even divine intelligence is considered to be “out there” and separate);

- the other knows all is alive and interconnected and pulsating with the same energy that shapes all existence urging it forward in its evolution.

Two important events are occurring right in the middle of 2013 (i.e. July) that I believe will help tip us towards a wider embrace of the second view of the world. They will help accelerate the shift in values…

View original post 227 more words

EPCOT’s Historicizing of Indigenous Culture

In EPCOT Centre, Walt Disney World, guests are invited to experience an area called, World Showcase. World Showcase attempts to “share with Guests the culture and cuisine of 11 countries” (Epcot Theme Park), and for several reasons the core of these eleven countries is the United States of America pavilion. The American Pavillion presents guests with a very stereotypical colonial representation of the United States, almost leaving Indigenous culture out entirely.

However, the one place that Indigenous culture is present within The American Pavillion is in their animatronics theatre show, The American Adventure. When guests enter the theatre they are greeted with twelve life-size statues, the ‘Spirits of America.‘ Each statue represents one believed aspect of United States history, these statues provide guests with the most stark contrast between Indigenous and Colonial culture. This is because the statute that represents the “Spirit of Tomorrow” is very clearly a white, colonial, woman holding baby. While the “Spirit of Heritage” is represented as a stereotypical, gentle, Indigenous woman.

Walt Disney World Resort, in which EPCOT is situated, is arguably one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world, and while these are just statues on the wall for a much larger show, their importance cannot be understated. By placing this Indigenous woman up against the white woman, it is creating a strong binary between the past and the future, and furthering the false myth that Indigenous culture is a thing of the past, and has no place in the present or future. Not to mention, there is no mention of which Indigenous community this woman comes from, thus generalizing the Indigenous culture as a whole.

As stated in Scherrer and Doohan’s article, “‘It’s not about believing’: Exploring the transformative potential of cultural acknowledgement in an Indigenous tourism context,” “in essence that they (as guests and facilitator of visitation by guests) need to understand why they can and can’t do certain things in order to change their behaviour (to be more respectful and act appropriately); that they first need to be educated[…]” (Doohan Scherrer 160). This plays a very important role in Disney’s representation of Indigenous culture, and that is because Disney must recognize the authoritative role that they are in. Disney is in a role as a very popular destination for guests from around the world, and they are not representing a major part of the culture of The United States properly, by giving the impression that Indigenous culture is a thing of the past, and thus furthering the myth of the ‘Vanishing Indian.’

To conclude this discussion of EPCOT, Marie Battiste argues that “acts of oppression tear[s] at the very spirit of individuals, denigrating the relevance and meaningfulness of their individual lives” (Battiste 217). This is very much the case in this example of The American Pavillion in EPCOT because Disney does not seem to be conscious of the fact that they are that they are harming a culture that is very present in North American culture by generalizing and historicizing the Indigenous culture, and furthering the ‘Vanishing Indian’ myth.

Works Cited

Battiste, Marie. “Unfolding the Lessons of Colonization.” (2004): 209-17. Web. 14 Nov. 2013.

Doohan, Kim, and Pascal Scherrer. “‘It’s Not About Believing’: Exploring The Transformative Potential of Cultural Acknowledgement in an Indigenous Tourism Context.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 54.2 (2013): 158-70. Scholars Portal. Web. 14 Nov. 2013.

“Epcot Theme Park.” Walt Disney World. Disney,. Web. 14 Nov. 2013. <https://disneyworld.disney.go.com/destinations/epcot/>.

Introduction to Indigenous Tourisim

For this blog I will taking a look at several different examples of how Indigenous Culture is represented by tourist destinations throughout North America, and how those representations trivialize the culture, as well as perpetrate the notion of the ‘Vanishing Indian.’ As mentioned briefly in my About page, this blog will be using the term ‘Vanishing Indian’ to discuss the idea the Western Culture aims to present the idea that Indigenous Culture is something of the past, and does not have a place in the modern world, which is an absurd concept. Through this blog I will be looking at four types of tourist destinations that represent Indigenous Culture such as, theme parks and resorts, and Museums, Casinos, and experiences available on Indigenous reserves. I will be looking at these different destinations from both colonizer and native perspectives and representations. Through looking at these four tourist spots in correlation to discussing several Indigenous works of fiction, as well as scholarly works related to this issue, such as Mary Louise Pratt’s Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation, I hope to come to a strong conclusion on tourism’s influence of the ‘Vanishing Indian’ myth.